Guide to SA Natural Areas & Greenway Trails

A: The Ashe Juniper

Much of the text and information for this point was taken by Alamo Area Master Naturalist Stan Drezek from the essay Mountain Cedar Friend or Foe? by COSA’s Peggy Spring's web article and Jan Wrede’s Texans Love Their Land , 1997.

Ashe Juniper

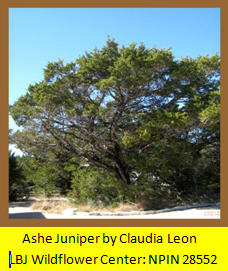

The Ashe Juniper (Juniperus ashei) is the dominant native tree species of the Texas Hill Country. While Ashe Juniper has existed in the Hill Country for tens of thousands of years, its recent relative dominance can be explained by human control of grassland fires and overgrazing of native grasses, thereby reducing fuel for fires.

OVERGRAZING & FIRE SUPPRESSION = ASHE JUNIPER DOMINANCE

The result is woody encroachment, especially by Ashe Juniper. Can you see its dominance in the areas along the Oak Loop Trail? Another particularly beautiful example of this dominance can be found in Friedrich Park’s Juniper Barrens Trail.

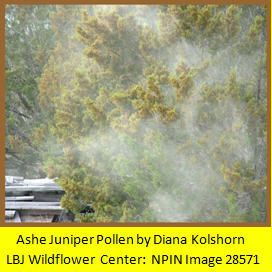

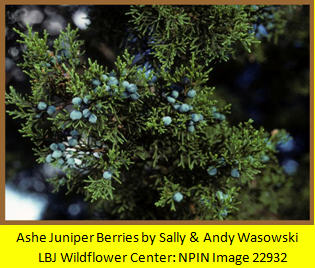

DIOECIOUS

The Ashe Juniper is an evergreen tree with tiny, scale-like leaves flattened into many little branches at the ends of twigs. There are separate male and female trees. From December to February the male trees turn golden brown with copious quantities of pollen, causing many locals to suffer from “cedar fever.” In the fall, the female trees produce the familiar, blue juniper berries, which are actually miniature cones. Can you find a female Ashe Juniper, whose “fruits” are eaten by many species of wildlife?

The bark becomes shaggy with age and shreds into long, narrow, irregular strips. Can you see some of this “old growth” Ashe Juniper along the trail? The wood of the Ashe Juniper is resistant to decay and insects.

REMOVAL? VS. LEAVE IT!

There is debate, subject to studies now being done, as to whether the environmental negative of the excess use of water by Ashe Juniper is outweighed by its positive contribution to soil stabilization and soil production, as well as providing shelter for wildlife. David Bamberger (see the April, 2010 Bamberger Ranch Journal) certainly makes the case for selective removal of Ashe Juniper.

However, Bamberger found that it was not so much the trees’ heavy use of water, but rather, as they form dense thickets, the trees actually prevent rain water from reaching the ground and, thus, percolating back into the groundwater supply. On the other hand, Bradford Wilcox’s 2010 paper in Geophysical Research Letters found “overgrazing and resultant soil degradation, not encroachment by woody plants, were the main culprits behind reductions in stream flows and recharging of groundwater….” It is probably safe to say that the dense thickets of junipers and the removal of grasses and plants due to overgrazing and the resulting water runoff are both serious contributors to the lowering of the water table.

"OLD GROWTH" JUNIPERS & GOLDEN-CHEEKED WARBLERS

There is no debate, however, as to the importance of the Ashe Juniper to the endangered Golden-cheeked Warbler (Dendroica chrysoparia). In March these birds return to Texas by flying over 1100 miles from wintering grounds in Guatemala and other Central American countries. It is the only bird species whose breeding grounds are confined to Texas, most notably the Texas Hill Country. All Golden-cheeked Warblers mate, reproduce and raise their babies in Texas. They weave their nests from the long, shaggy strips of “old growth” juniper and spider webs. They feed themselves and their young on the insects and arthropods living on Ashe Juniper, Red Oaks, Live Oaks, and Cedar Elms. Despite the lack of steep-sided canyons and its small area in the middle of an urban expanse, Park Naturalist Wendy Leonard observed and followed a Golden-cheeked Warbler in Pil Hardberger Park (East) on March 11. 2012.

Because of the impact of land development in reducing “old growth” juniper, governmental agencies are working on Habitat Conservation Plans to protect this precious resource. Do you realize that if we had no “old growth” juniper, the Golden-cheeked Warbler would cease to exist?