Louveciennes

|

Text excerpts from the book "The Chateaux of France" by Daniel Wheeler The Vendome Press 1979 ISBN 0-86565-036-5 |

|

|

After 1750, so pervasive was the mood of reform, in reaction against

the decadence of life under Louis XV, that one of the major symbols

of the new spirit is the little freestanding pavilion at Louveciennes.

The irony is that the structure was commissioned by none other

than the Comtesse du Barry, Louis XV's last mistress and the archsymbol

of all that contemporaries considered effete and self indulgent

in France's ancien regime. No one could have been less interested

in moral regeneration or the politics of revolution than Jeanne

Béçu du Barry (1743-1793). Kind, good -humored,

and devastatingly beautiful, she existed solely to amuse a bored

and aging monarch, who, in gratitude for the services she rendered,

all but suffocated her with favors. One of these was the gift

of Louveciennes, a small chateau built in 1681 [just up the road

from the pavilion, probably built 1700 -ed.] by Louis XIV for Arnold de Ville , the Liegois

who had designed the famous Marly machine for pumping water to

the King's fountains [at the chateaux of Marly and Versailles].

Mme du Barry had none of the intellectual ambition of her predecessor

at court, the Marquise de Pompadour, but she was a lady of fashion

and eagerly followed the new trend just as soon as it set in.

This was Neoclassicism, a fresh, highly purified interpretation

of Greco-Roman forms designed to purge the Rococo, or Late Baroque,

of its soft, curvilinear graces, and thus to parallel in art and

architecture the rigor and rectitude then being urged in the socioeconomic

dimension of life. When the latter got out of hand, it exploded

into the violence of the French Revolution. As always in a time

of crisis, the arts did just the opposite. Instead of destroying,

they yielded an absolute plethora of enduring masterpieces. Among

the first of these was Mme du Barry's pavilion at Louveciennes.

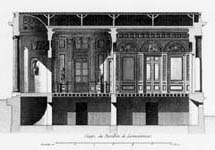

Delighted with her new toy - the chateau - La du Barry immediately commissioned a restoration from Jacques-Ange Gabriel, the great exponent of the style Louis XV at its most elegant and refined. But the dwelling remained small, and so the châtelaine turned to Claude-Nicholas Ledoux, then largely unknown, and asked him to design a supplementary pavilion consisting of nothing but a few reception rooms. what the young master produced is so simple, severe, and elementary that it borders on pure abstraction, and more than a palace of sensuous delight, it seems a temple for the votive rites of Vestal Virgins. In this crisply articulated, oblong box, not even a pediment, but merely a balustrade, crowns the central bay; thus, hardly a diagonal or an arabesque obtrudes within a realm derived directly from those most primary of forms, the cube and the sphere. Paradoxically - and characteristically - Mme Dubarry called it a "folly." Still, when it came to the exterior decor, she rejected the true follies - and gorgeous ones at that - painted by Jean-Honoré Fragonard and ordered a whole new cycle of murals from Joseph-Marie Vien. Although a lesser artist than Fragonard, Vien was one of the first of the Neoclassicizing painters and the teacher of the style's greatest master, Jacques-Louis David. Gouthière prepared bronzes and Pajou sculptures. Once completed, the Louveciennes pavilion caused a furor, for clearly the new age had arrived. No one could have recognized it better than Louis XV, whose own Pompadour had already said: Après nous le déluge! Thus, when Mme du Barry marked the inaugural with a great banquet, the King attended. After Louis XV's death of smallpox in 1774, when she personally attended the King despite the risk of her own infection, Mme du Barry suffered many indignities, beginning with a period of confinement in a convent - where she managed to make the nuns like her. Too faithful to the memory of Louis XV to emigrate, she became the butt of the most rabid Revolutionary hatred. Finally condemned, the former royal favorite mounted the scaffold on December 8,1793, and at age fifty submitted to the guillotine.

Much later, after the ground had shifted under the Ledoux pavilion,

threatening its structure, M.F. Coty moved the edifice, stone

by stone, to another site. Unfortunately, he also added an attic

story and installed a swimming pool in the basement. The interior

decor was reconstituted from old engravings. Louveciennes remains

a private estate, owned by M.V. Moritz [now deceased].

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Photography: David Pendery |